Two close friends have given birth in the last two months. My sister-in-law is due with her first any day now.

Next week we are welcoming 6th graders to their first secondary camp, and drinking in the final camp experience with our fresh graduates. I will have a third grader in the Fall, which I’ve always thought of as the first Big Kid grade. Seven adults have just formed a rotation to sit at home with Dad on the Sundays he’s not well enough to attend church, so that Mom doesn’t have to miss.

Beginnings and endings. It seems there’s never one without the other. Might as well find a good snow cone place.

Welcome to The Paradox Paper, a monthly newsletter that honors the everyday paradox of a life with Jesus. If a friend forwarded you this email, click here to subscribe:

In this edition:

Another biography for the Shelf of Saints

A series I started out of a sense of artistic duty, and then couldn’t put down

The wordless conversation I had with the Lord the night my first child was born

A song that reminds me: all that is evil is not final

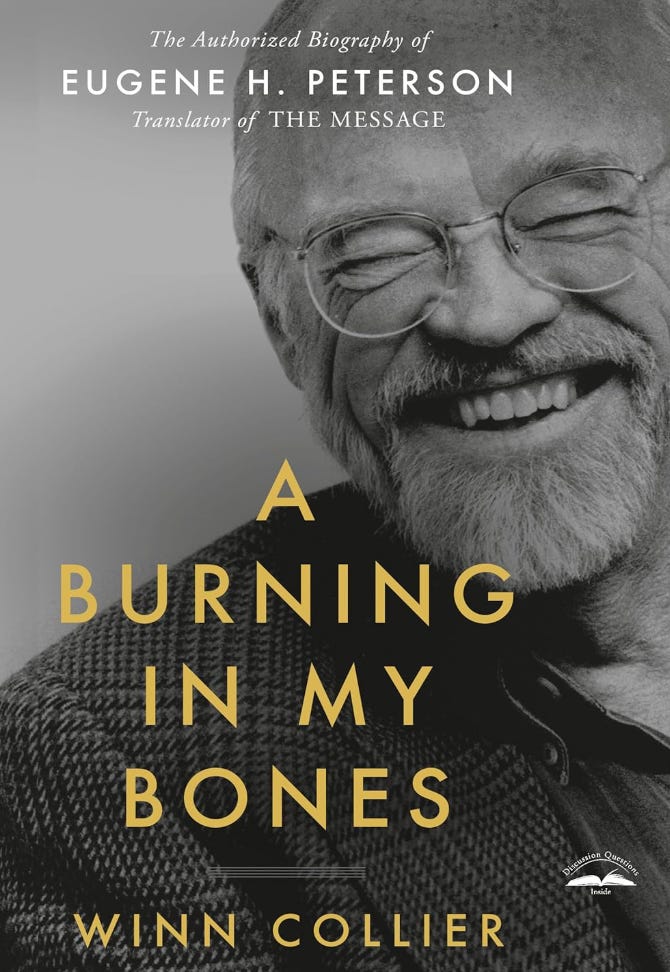

A Burning In My Bones, Winn Collier

The best biographies (but especially the Christian ones) are those that tell the full story of a life, failures and all. Winn’s friendship with Eugene and his commitment to honest and beautiful writing make this a moving account of a man who lived a whole life—failures and all—in the direction of Christ and for the good of His Church. I have recommended it to my pastor, my friends in seminary, and anyone else who cares (or pretends to care) what I think about books. I will return to it over and over, and assign it to my boys someday.

The Gilead Series, Marilynne Robinson

Marilynne Robinson was mentioned as one of Eugene Peterson’s favorite authors, which gave me the push I needed to finally read her work. Reading has not come naturally to me. I practice reading because I love to write and want to do it well. Granted, the more I practice the more I enjoy it and the greater my capacity for difficult books becomes. Still, there are always books on the “self-assigned homework” list. You know. Books that I should read for what they will teach me about writing, but don’t feel excited about. Gilead was one of those books. I expected to learn from Robinson’s writing. I did not expect to be moved—to be compelled—but I was.

For starters, the similarities between Robinson’s characters and my own life were startling. I was the unexpected child of my father’s old age, the product of a marriage with a twenty year age gap, and raised in a tiny town on the Western plains where my dad was a theology professor. John Ames is a small town pastor in the final years of his life, who begins writing a memoir for his seven year old son. Ames is thirty years older than his wife Lila, having married her (at her suggestion) after a long and lonely widowerhood. What follows is a poignant account of all the things Ames wants Robbie to know, but won’t be around to tell him in person. Sparse, earthy, and beautiful.

When I started Gilead I didn’t know it was the first in a series of four. As much as I enjoyed the first novel, the second, Home, is my favorite of the series.

There’s no way a newborn falls off a third floor balcony. Not by themselves. But that’s what I dreamed about the week after my first child was born. In the few hours a night I was able to sleep my brain cooked up all manner of implausible horrors. I’d jolt awake, a scream in my throat, to see him breathing deep and easy. Safe in his bassinet. Entirely unbothered by his helplessness. Neither of us was bothered much by that, actually. It was my own helplessness that terrified me.

Truitt made his entrance into the world via our bathroom floor six days after the first anniversary of my brother’s suicide. “Here he is,” Nicole said, in the same tone she might’ve alerted us to the arrival of a DoorDash delivery. A few seconds of silence as he gathered that first wet breath. Then he screamed. The garbled, indignant scream of tiny wet things unaccustomed to air and light.

I heard a smile in Nicole’s voice. “He looks great! Let’s stand up.” It was impossible, given the strange mix of jell-o and rigor mortis that had overtaken my legs, but shaking and sweating and bleeding, I stood.

“You take her, I’ll take him,” she directed Trevor. “We’re going to the bed.” The huge absorbent pads the other midwife had magicked into place crinkled under my feet as I waddled the few yards from bathroom to bedroom. Nicole held the still-attached Truitt, crawling on her knees behind us to keep from tangling the cord.

“Take your baby,” she said, laying him on my chest once we’d done the delicate dance of getting me into bed. Two hours later the three of us were clean, fed, tucked in, and alone in our dark apartment.

I tried to keep him on my chest while I slept. I did. But the warmth and weight of him. The press of his downy head, utterly dependent against my sternum. I just couldn’t do it. The pressure of his tiny body compounded the weight of responsibility pressing in around my soul. I eased him away from my heart and resettled him in the bassinet. His breaths came steady and full, as if none of the pain I’d carried for the last year had crossed the umbilical cord. He breathed like someone unfettered, unbound. Free. Free.

My fingers stole around my middle above my empty, bleeding womb. The relief of no more over-fullness, I expected. No one warned me about the emptiness. The hollow space where organs used to be and hadn’t yet returned. In two days I’d tell Nicole, “It feels like my insides are floating away.” Per usual she would be the complete opposite of alarmed. “Oh, they are. But not away. They’re floating back home.”

I stared at my boy by the faint glow of the nightlight and breathed with him, the awareness that I could no longer breathe for him like an exposed nerve within me. So many things I do for him, and so many more I’d like to do but can’t. I feed him, but can’t make him eat. I can’t make him grow. I hold him and cover him, but I can’t set his temperature with a keypad. I house him and clothe him. I sing to him and play with him. I bring him to the park, to the doctor, to the altar. But I can’t make him breathe. I can’t give him life. Couldn’t, even when he shared my lungs. Even then, his life happened to me.

We breathe in together, and I exhale surrender.

Inhale: I cannot keep my son alive.

Exhale: Yahweh carries us along.

Listen to me, descendants of Jacob, all you who remain in Israel.

I have cared for you since you were born. Yes, I carried you before you were born.

I will be your God throughout your lifetime—until your hair is white with age.

I made you, and I will care for you. I will carry you along and save you.

- Isaiah 46:3-4

God loves you. Hold the paradox. Don’t panic. See you in next month!

-Steph

If you enjoyed this edition of The Paradox Paper, consider sharing it! Your sharing encourages others to read, which encourages me to write.